Suffering

and Pain

See how Spanish artists explored the sentient experience of suffering and pain.

Suffering and pain are topics that have fascinated artists and their audiences from the Middle Ages to modernity. Appraised from a variety of perspectives, they often expose injustices or else point to moments of extreme personal tension, eliding the distance between viewer and viewed by triggering outpourings of identification and empathy.

As aspects of the judicial process, suffering and pain serve both as punishments and as mechanisms for rehabilitation, depriving convicts either of their freedom or of life itself. For those who followed in Christ’s footsteps, subjecting themselves to the horrors of martyrdom, the experience of suffering and pain offered a formula for emulating his example while establishing models of exemplary devotion. Comparable sentiments are offered by treatments of old age and infirmity, which explore the importance of approaching death with grace and dignity, as well as studies of asceticism, where procedures of self-inflicted suffering enable individuals to overcome the temptations of the flesh or atone for the sins of the past.

A topic of particular importance is the suffering and pain caused by sexual guilt, which can produce some of the most extreme and self-destructive behaviours. A common denominator in each instance concerns how experiences that are personal and intransmissible can be captured in visual form and thereby made real for audiences.

Interior of a Prison

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, c. 1793–94.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

Goya’s painting offers a poignant exploration of the relationship between crime and punishment, depicting the suffering of seven prisoners, each with hands and feet bound by heavy chains. While some sit or lean against the prison walls, consumed by their own thoughts, another lies awkwardly on the ground, his head angled towards the viewer. The atmosphere, which is one of silent and unremitting gloom, suggests an interest in questions of penal reform and the recognition of inalienable human rights.

Crucifixion

The Durham Master, Early sixteenth century.

The Galilee Chapel, Durham Cathedral.

Depicted in a battered and brutalized state, with a body full of welts and contusions, Christ hangs limply on the cross, his head drooping lifelessly downwards. While St John the Apostle clasps his hands together in prayer, and Mary Magdalene kneels to embrace the wood of the cross, the holy women on either side adopt a range of postures, shedding tears at the death of their master. Painted in a distinctively stylized manner, the trees and buildings in the background hint at the prospect of impending salvation.

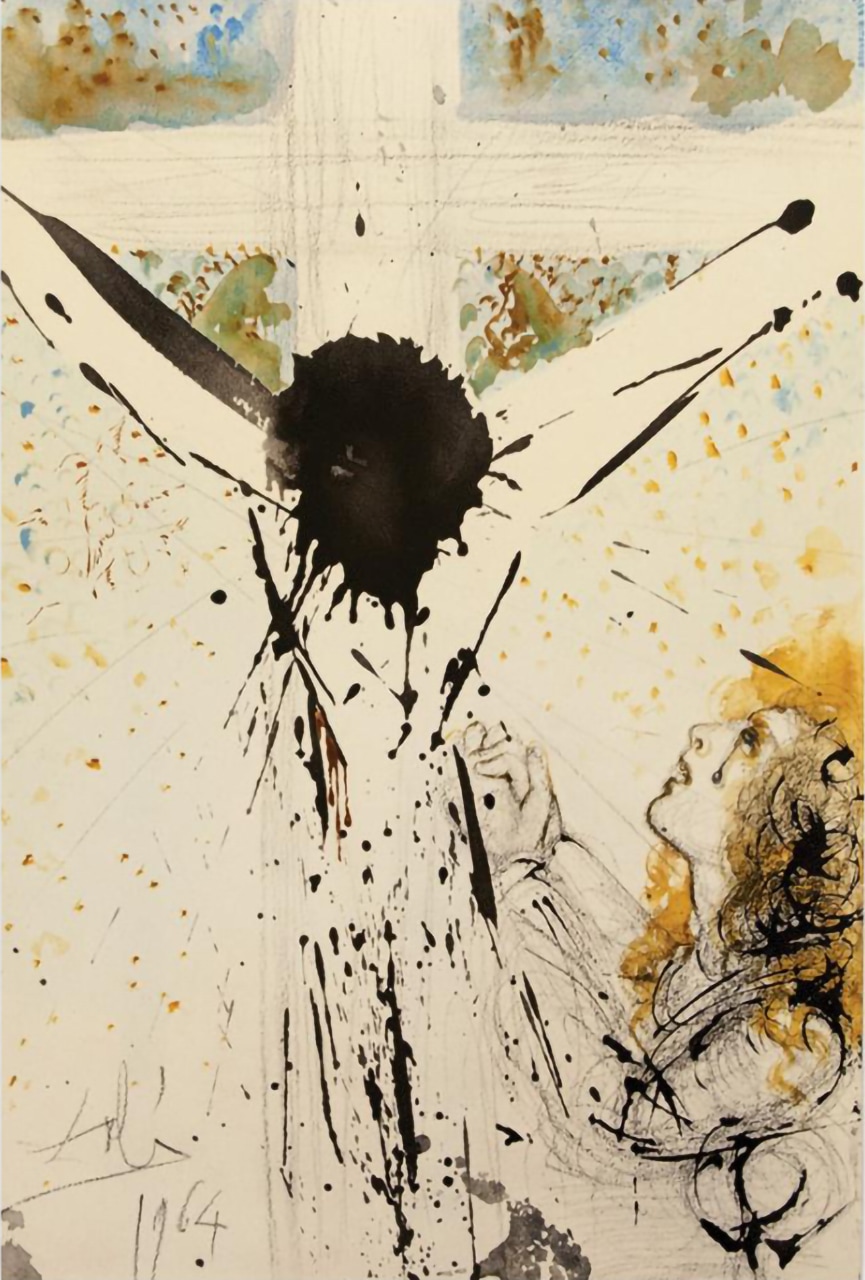

Tolle, tolle, crucifige eum

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1967–69.

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

Dalí has reinvented the traditional theme of the Crucifixion through a range of visual devices and effects. Christ’s upper body is seen from above, while Mary Magdalene is presented at eye level. Christ is sketched in black ink, the ground is undefined, and yellow dots float in space. Based on Dalí’s theory of nuclear mysticism, the triangular configuration, which is here formed by Christ’s arms, his head, and the horizontal bar of the cross, evokes Dalí’s idea of the structure of the atom. The head, reduced to a splash, represents the nucleus.

St Bartholomew

Unknown artist active in Granada, Late seventeenth century.

University College, Durham University, 18.1214.

Produced in Granada, these two large-scale artworks offer representations of St Bartholomew in his glorious post-resurrection state. Having been flayed alive for preaching the word of God, the saint is characterized as an authoritative and imposing figure, with elegant robes and a full beard flecked with tinges of grey. The knife in Bartholomew’s right hand (unfortunately destroyed in Gaviria’s sculpture) offers a reference to the uniquely harrowing nature of his martyrdom, while the book in his left alludes both to his activity as a preacher and to the concomitant transformation of skin into properties such as leather and parchment, the materials from which books are made.

Read the in-depth commentarySt Bartholomew

Bernabé de Gaviria, 1600-1622.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

The Martyrdom of St Andrew

Luis Tristán de Escamilla, c. 1616–24.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

This painting depicts the fate of St Andrew, who, according to tradition, was suspended on a cross for three days before dying. The composition is notable for the illumination of the saint’s musculature and his elongated body shape, factors that betray a debt to the artist’s former mentor, El Greco, as well to the paintings that he encountered during his visit to Rome between approximately 1606 and 1613. In the background, the setting sun and rising moon establish an impression of cosmic importance, characterizing the torture as a product of the never-ending conflict between good and evil.

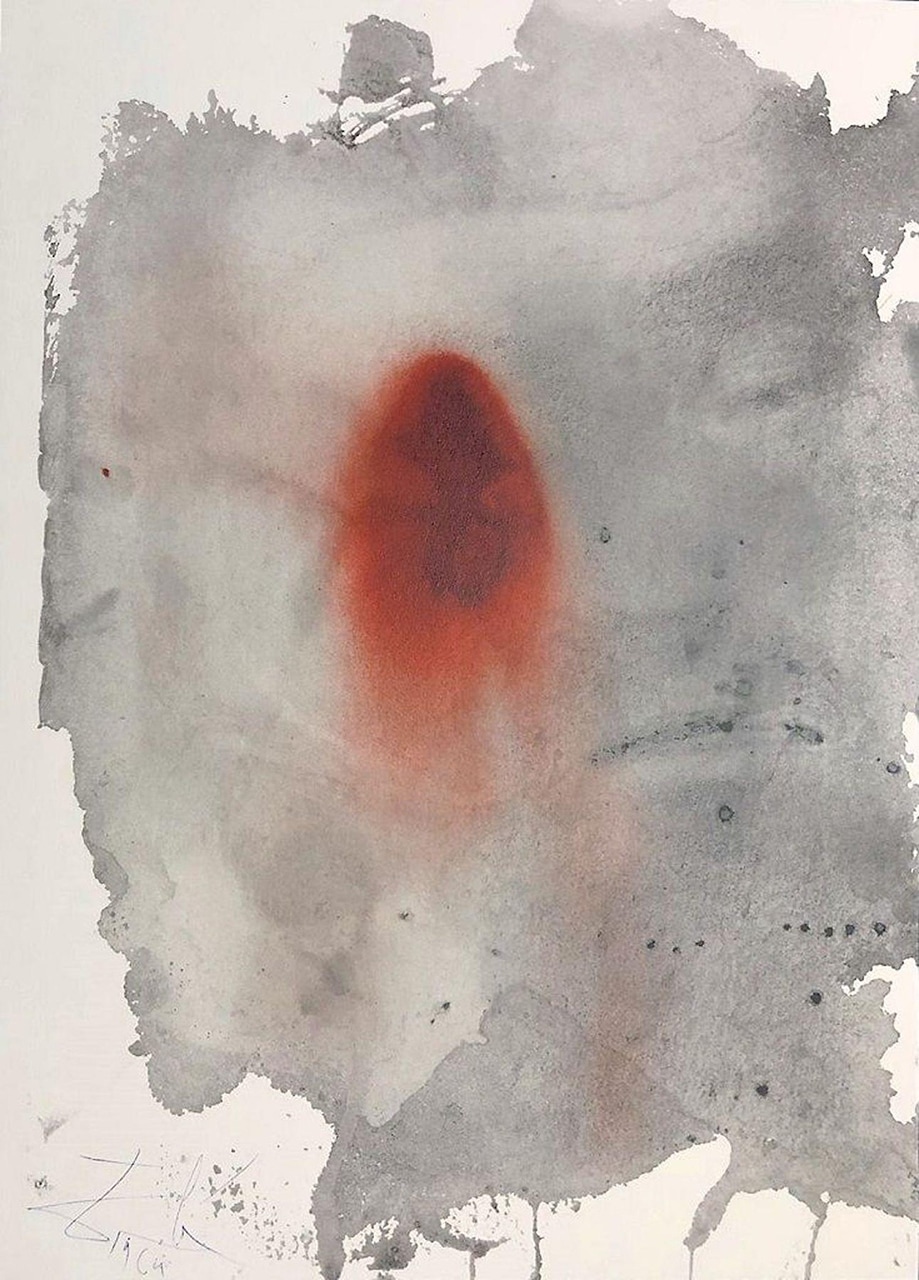

Ego sum vermis et non homo

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1964.

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

In this arresting and innovative self-portrait, Dalí advances an insight into the rigours of age and the inevitability of death. Reduced to a flap of flayed skin, the artist’s face—replete with trademark handlebar moustache—appears almost in the guise of a death mask, while the burrowing worm, represented by the vibrant red shape over his right eye, gnaws its way inexorably into his skull. In contradistinction to the violence of the image, the sleep-like peacefulness of the artist’s expression points to the reassurance of faith.

Jacob

Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1640–45.

Auckland Castle, Bishop Auckland.

Zurbarán depicts Jacob as a frail old man leaning on a staff at the end of a long and productive life. The composition is most notable for the low line of the horizon, which imbues it with a sense of imposing monumentality, and for the pronounced curvature of Jacob’s spine, which characterizes him as a figure worn down by the withering rigours of age. With eyes hidden from view, he seems lost in thought, almost certainly contemplating the inevitability of his fate.

St Jerome

Antonio de Puga, 1636 (dated).

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

In this painting, which is the only one that he signed, Puga captures St Jerome at a moment of intense personal tension. Having been assailed by sexual thoughts, the saint grips a crucifix in one hand and a stone in the other, determined to make himself suffer until his soul is purged of iniquity. The subject provides the perfect analogue to contemporary debates concerning sexual guilt, self-harming, and the difficulty of supressing instinctive emotions.

The Penitent Magdalene

Mateo Cerezo, c. 1665–66.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

These two painted treatments of Mary Magdalene offer insights into questions of sexual guilt and how suffering and pain are embraced in the Christian tradition as mechanisms for self-improvement. Having spent her life as a harlot, Mary recognizes the error of her ways and repents. In the first painting, by Maíno, she is depicted at a point of emerging self-awareness, while in the second, by Cerezo, her tear-stained face emphasizes the extent of her guilt and the importance of contrition.

Read the in-depth commentaryThe Penitent Magdalene

Fray Juan Bautista Maíno, c. 1609.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Two Girls Playing in a Vineyard with a Small Dog

Pedro Núñez de Villavicencio, c. 1670.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Set in a vineyard, Núñez de Villavicencio’s painting captures a moment of spontaneous interaction between two young impoverished girls. While the figure on the left responds with wide-eyed concern to the dog that tears aggressively at the hem of her skirts, her sullen-faced companion directs an outstretched finger towards the shattered fruit—most likely a zatta melon—in the lower left-hand corner. In her other hand she holds an object, most likely a glass jar with a sprig of leaves, on which she affixes her gaze as if drowning her sorrows.