People

and Places

Discover how artists engage with the ideals and realities of places and their inhabitants.

Spanish artists engage in various ways with the ideals and the realities of places and the people who inhabit them. The works in this gallery are based on direct observation, the imagination, or a combination of both.

Several paintings relate to locations that were of major significance in the collective psyche of seventeenth-century Spain. Two of the most notable are Seville, the wealthiest and most cosmopolitan city of the time, and the Monastery of Montserrat, which houses one of the most venerated Marian statues of the Iberian Peninsula. Going beyond the mere recording of topographical reality, Spanish artists reflected the ideological and religious beliefs that shaped the identity of these places. Other paintings in this section demonstrate how artists found creative solutions for visualizing legendary ancient sites or imaginary places, which are only known through biblical and apocryphal accounts.

The portraits included here reveal different artistic approaches to fashioning the identities of high-ranking individuals in Spanish society. While mid-seventeenth-century artists placed emphasis on the sitter’s social status through clothing and accessories, those who were active in the late eighteenth focused on their expressions so as to capture their character.

The Surrender of Seville to Ferdinand III, King of Castile and Leon

Circle of Francisco Pacheco, c. 1634–50.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

The turbaned Muslim leader of Seville, Al-Xataf, surrenders the city in 1248 to the Christian King, Ferdinand III of Castile (1201?–56), by kneeling to present its key on a golden platter. Hovering in the sky is a vision of the Virgin Mary, who allegedly offered Ferdinand support during the long siege. The faint halo above his head alludes to the seventeenth-century campaign to make him a saint. Dominating the skyline of the detailed view of Seville is the minaret of the former mosque, which was converted into the Giralda, the bell tower and weathervane of Seville Cathedral.

Saint Ferdinand

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, c. 1671.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Murillo depicts Ferdinand III, the medieval saint-king, in a naturalistic manner, with stubbled chin and baggy eyes. The portrait is the result of the artist’s encounter with Ferdinand’s entombed yet uncorrupted body in Seville Cathedral in April 1671. The Latin inscription defines him as a king who ended the dominion of Islam in the Iberian Peninsula and thereby restored the ‘Hispanic world’. Ferdinand holds his saintly symbols, an unsheathed sword and a globe, in his hands, while a faintly gleaming halo is revealed by the putti (or child angels) above.

The Virgin of Montserrat with a Donor

Juan Andrés Rizi , c. 1645.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

The ancient statue of the black Virgin of the Monastery of Montserrat in Catalonia is one of the most venerated Marian images in Spain. The artist has depicted her seated on a rock against the dramatic mountain landscape surrounding the Monastery and its Church, where the statue is located. The kneeling figure on the left, either a monk or a religious patron, looks out of the picture, inviting us to venerate the Virgin, just as he does.

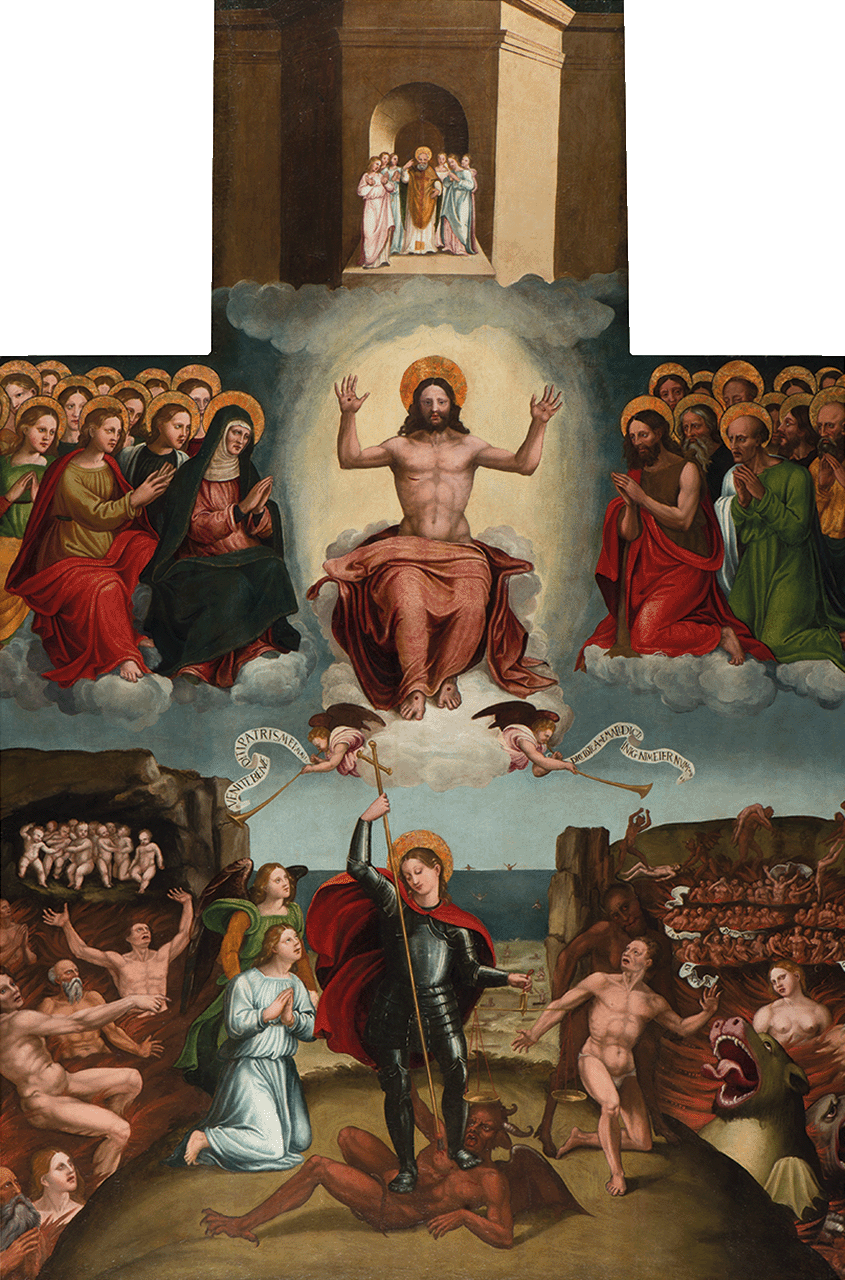

The Last Judgement with the Archangel Michael

The Master of Alzira, c. 1525–50.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

This large panel depicts the Last Judgement, as foretold by Revelation 20:11–15, where it is said that Jesus will return to judge humanity and decide who will go to heaven and who will be thrown into hell. The dramatic narrative is divided into three parts: at the top St Peter holds the keys to the gates of heaven; in the middle a muscular image of Christ sits in judgement surrounded by saints; and at the bottom St Michael is shown defeating the Devil while sinners burn in the fires of hell.

Turris Babel

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1967.

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

Dalí has depicted the legendary Tower of Babel, which, according to the Bible, was built after the Flood as a stairway to heaven. Angered by such hubris, God created different languages so that people would no longer understand one another and so be forced to abandon their project. On the one hand, the story serves to explain the existence of multiple languages across the earth, and on the other, it serves as a warning about the arrogant pursuit of power.

A Levitation of Saint Francis

After Jusepe de Ribera, c. 1630–50.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

In this painting, which was formerly attributed to the circle of Francisco de Zurbarán and is now attributed to that of Ribera, St Francis is depicted in a moment of spiritual ecstasy, displaying the power to levitate as he ascends high into the sky and upwards towards heaven. While his haggard face and reddened eyes suggest a lifetime of extreme ascetic denial, his shabby robes serve as a reference to his commitment to poverty. As he extends his arms outwards, the marks of the Crucifixion—the stigmata—become visible on his hands, side, and feet.

A Carmelite

Fray Juan Bautista Maíno, 1620–25.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

The enigmatic gaze and distinctive face of Maíno’s friar suggest that this may be a portrait of a real person, possibly the founder or the architect of the church that he holds in his hands. The friar’s white cowl and brown tunic are those of a Carmelite, a contemplative religious order that produced mystics such as St Teresa of Ávila and St John of the Cross. While the identity of the friar remains unknown, the dramatic sky gives the image a luminous quality, heightening the sense that he may well be a saint.

Portrait of a Young Boy Holding a Lance

Juan van der Hamen y León, c. 1620–30.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

This portrait shows a young boy dressed in a rich costume and holding a short lance. The artist is Juan van der Hamen y León, the only rival to Velázquez as court portraitist in the early years of the reign of Philip IV. Primarily known today as a still-life painter, he portrayed several significant members of the court. While the boy’s identity is unknown, there are possible links to the family of Gaspar de Guzmán, the Count-Duke of Olivares (1587–1645), the powerful royal favourite of King Philip IV, who ruled from 1621 to 1665.

Portrait of Juan Antonio Meléndez Valdés

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, 1797.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

The poet and magistrate, Juan Antonio Meléndez Valdés (1754–1817), belonged to a circle of Spanish Enlightenment thinkers who aimed to reform society. In this intimate portrait he is placed against a dark background, wearing a dark red coat and a white shirt. He is looking out at us with a serious expression, lips slightly parted as if about to speak. Goya’s inscription in the lower part is a dedication to the sitter, describing him as his ‘friend’.