Animals

and Objects

Discover how Spanish artworks exploit the symbolic potential of animals and objects.

Animals and objects are often important elements in narrative paintings, helping to convey symbolic meaning pertinent to a story while also showing off an artist’s mimetic skills. In portraiture, animals and objects serve to convey information about the figure’s character and life.

By the late sixteenth century, the interest in depicting objects was such that still-life painting emerged across Europe as a category in its own right. In Spain, the term applied to this genre was ‘bodegón’ (‘bodegones’ in plural).

Still-life paintings were initially collected by a minority of enthusiasts but eventually reached larger audiences. The pioneering austere representations of fruit and vegetables, carefully arranged in shallow window frames by the Toledan painter, Juan Sánchez Cotán, were particularly influential. With each element sharply lit against a dark background, such compositions invite us to reappraise the significance and beauty of humble objects.

Many other artists followed Sánchez Cotán’s example. In the seventeenth century, artists specialized in sub-categories of still life, such as flower painting, which became popular for the decoration of palatial homes and ecclesiastical palaces.

Mater Dolorosa

Attributed to Jerónimo Jacinto Espinosa, Seventeenth century.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Depicted in a poignantly grief-stricken state, the Virgin Mary gazes ruefully downwards at the Arma Christi or Instruments of the Passion, focusing her attentions on the crown of thorns, the nails used to secure Christ to the cross, the blood-tipped spear that penetrated his side, and the shroud in which his lifeless body was later wrapped. Despite the consolation of salvation, the tears streaming down her face encourage audiences to engage in acts of mimetic and empathic engagement, affixing their attentions on the all too human—and all too familiar—nature of her loss.

The Penitent Magdalene

Luis Tristán de Escamilla, c. 1620–24.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Captured at a moment of heightened emotional intensity, with tears visible on her cheeks, Mary Magdalene clasps her hands together in prayer while gazing downwards at the collection of objects on the makeshift altar before her. In addition to the skull, which serves as a ubiquitous symbol of mortality, the cross and the books function as references to her love of Christ and her commitment to Christian dogma. Most ominous, however, is the bloodstained discipline (or scourge), which reveals that she has spent her days punishing her flesh in order to purify her soul.

Benjamin

Arthur Pond, 1756.

Auckland Castle, Bishop Auckland.

Zurbarán portrays Issachar as a humble farmer, stooping forwards under the weight of the load on his back. His company on the road is a donkey, the sorrowful face of which mirrors the state of its master. By contrast, Benjamin, Jacob’s most beloved son, is depicted as a finely dressed youth. He is accompanied by a wolf on a chain, recalling the description of him as ‘a ravenous wolf’ (Genesis 49:27). In both images only the heads of the animals are visible, encouraging viewers to imagine the setting beyond the frame of the canvas.

Read the in-depth commentaryIssachar

Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1640–45.

Auckland Castle, Bishop Auckland.

La Perra de Graus

Francisco Bayeu y Subías, c. 1788–89.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

This carefully depicted dog is a bitch from an Aragonese breed. She is dozing, paws stretched forward and muzzle placed next to her front paws. The different markings and textures of her coat are carefully rendered. The artist’s interest in this subject was connected to a project to provide King Charles III of Spain with dogs from the ancient Aragonese breed for reviving the stock of the royal pack. Yet the dog was never used for breeding, possibly because of its lack of pedigree.

Still Life with Asparagus, Artichokes, Lemons, and Cherries

Attributed to Blas de Ledesma , c. 1602–14.

The Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, B.M.69.

Ledesma’s picture is representative of Spanish still-life painting, which developed as an independent genre from the late sixteenth century onwards. In the centre is a basket with asparagus and artichokes. On either side in the foreground are two bowls containing bright yellow lemons. Two cherry branches frame the composition from above. The strict symmetry of the picture is softened by the three loose lemons and the asparagus that is placed obliquely in the lower foreground.

Still Life with Basket of Fruit, Melon, and Grapes

Attributed to the Stirling-Maxwell Master, c. 1610–40.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Following the prototype of Spanish still-life painting established by Juan Sánchez Cotán in around 1600, the artist has depicted common foodstuffs in a window frame, which is evocative of a pantry or larder. On the ledge, a basket containing figs, grapes, and vine leaves is flanked on either side by two apricots. Red peppers, blue grapes, and a green-yellow melon hang by threads from above. On the right, a thistle appears from behind the ledge, a detail that contributes to the illusion of spatial depth.

Still Life with a Large Array of Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Stone Pedestal

Juan de Arellano, c. 1660–76.

The Spanish Gallery, Bishop Auckland.

Arellano presents us with an idealized view of a fresh bouquet of flowers in a vase standing on a plinth. In reality, it is impossible to see this mix of fresh flowers all at once, because they grow and blossom at different times of the year. Most are in full bloom, while some rose buds are still to open up. Painted with extraordinary skill, the artist invites us to admire his pictorial achievements, marvel at nature, and reflect on the passage of time. Such flower paintings were popular for the decoration of palatial homes and ecclesiastical interiors.

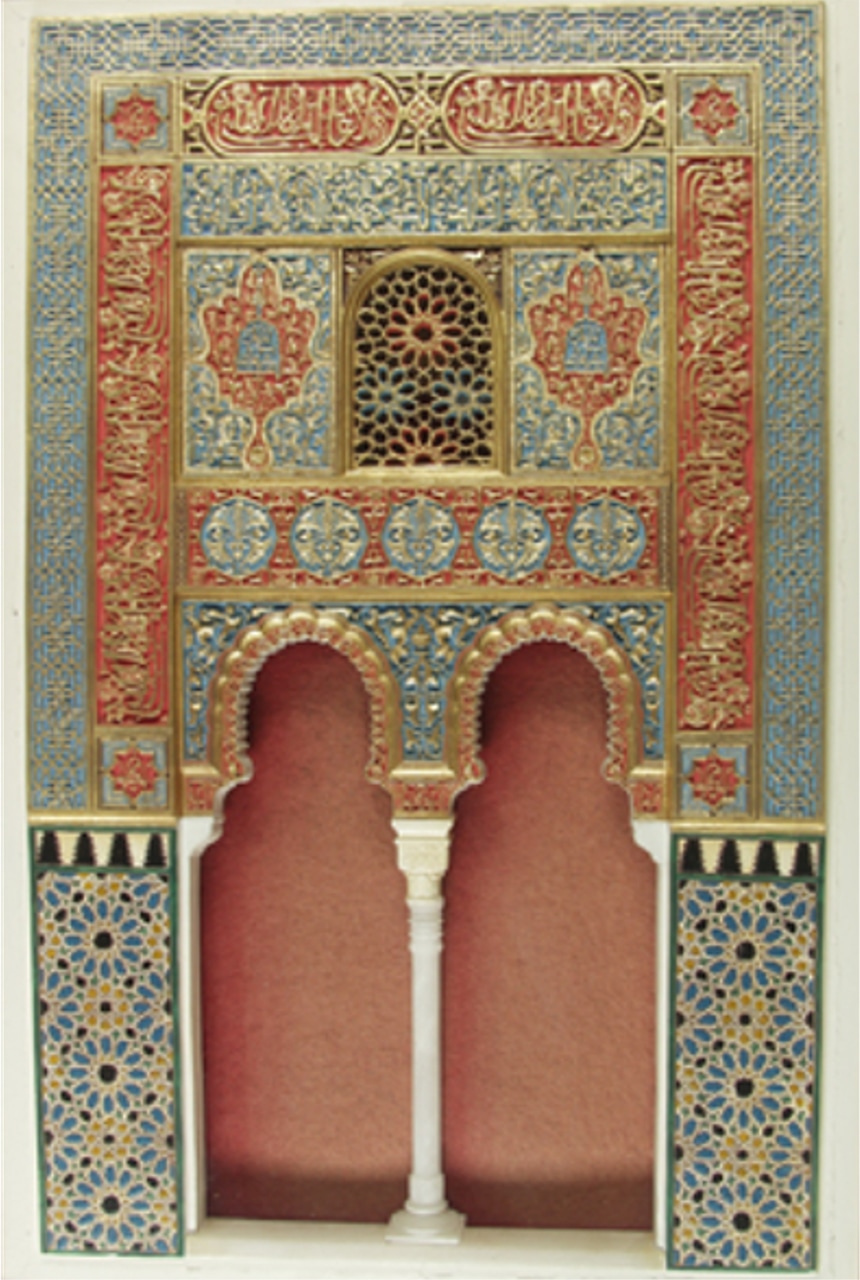

Architectural model of a façade of the Alhambra Palace, Granada

Unknown artist, c. 1890.

The Oriental Museum, Durham University.

This nineteenth-century architectural model is inspired by the Alhambra, the famous palace-fortress in Granada, built by the Nasrid dynasty during the last period of Islamic rule in the Iberian Peninsula (711–1492). In the nineteenth century foreign travellers greatly admired the sumptuous architecture and décor of the building, which struck them as exotic and oriental. As tourism developed, miniature versions, like this one, were produced in specialist workshops in Granada and sold to tourists as expensive souvenirs.