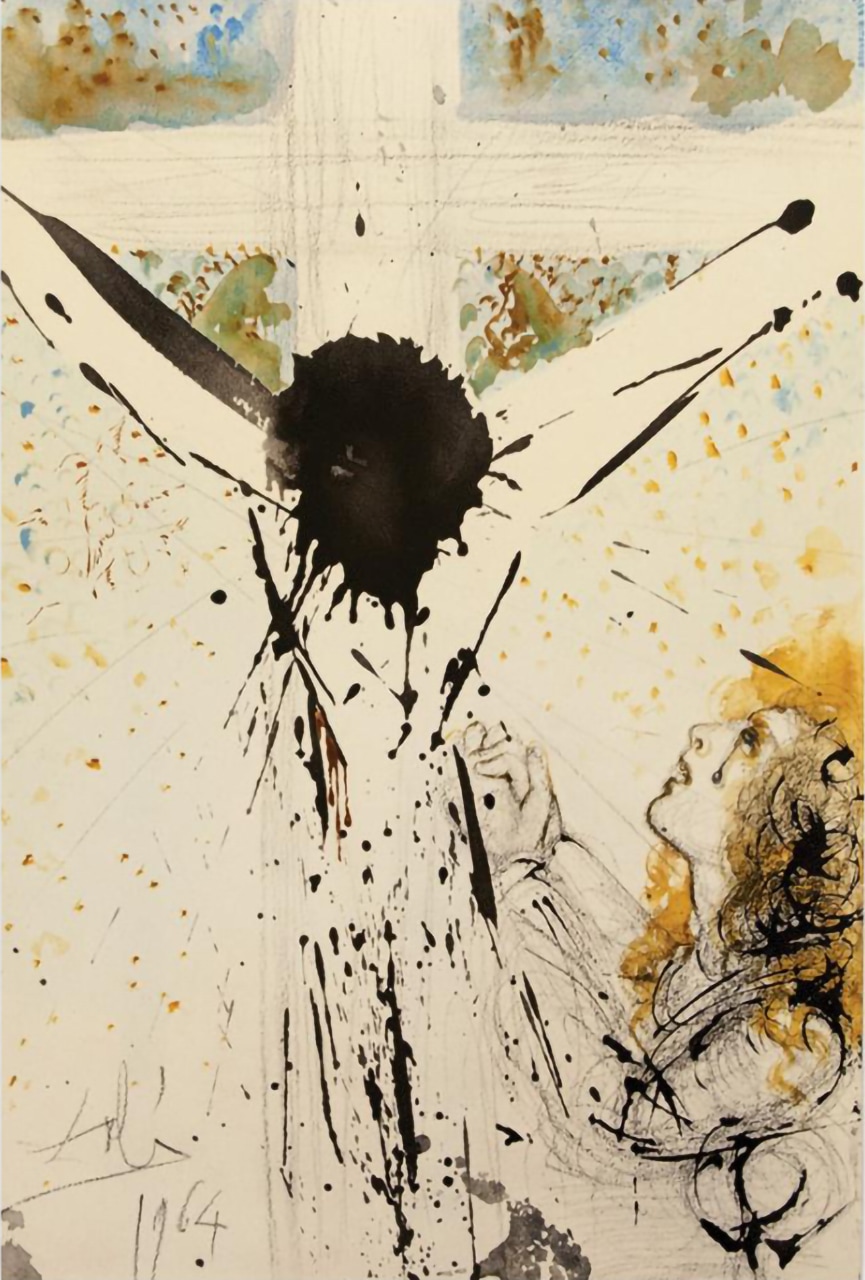

Tolle, tolle, crucifige eum

The lithograph is based on an original 1964 drawing in which Dalí used a range of graphic effects and visual devices to reinvent the traditional image of Christ on the Cross. Combining different viewpoints, the artist makes us look at Christ’s upper body from above, but we see the cross itself and the figure of Mary from directly ahead. The cross is faintly indicated, while Christ’s figure is sketched boldly in ink. The lines defining the arms and the torso converge towards Christ’s drooping head, which is formed by a splash of black ink, pointing downwards and constituting the focus of the image, with fine lines radiating from it. At the top of the composition, the sky is suggested in blue, and divine light in ochre and yellow. Yet below this, splatters of black ink and the broken lines simultaneously suggest blood dripping down and the disintegration of Christ’s body. His feet are not visible, the ground is undefined, and, in the surrounding space, yellow dots are dispersed on white ground, just as dematerializing particles floating in space. These suggest a spiritual lightness that forms a contrast with the materiality of the figure of Mary Magdalene at lower right. Densely drawn in ink and featuring long golden hair, she expresses earthly suffering: a heavy tear has fallen from her eye, her clasped hands are raised, and her mouth is wide open as she laments Christ’s death.

The image relates to Dalí’s earlier oil paintings such as Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubicos, 1953–54, Metropolitan Museum of Art), which shows Christ suspended in mid-air with Dalí’s wife Gala disguised as Mary Magdalene below. In addition, the lithograph and the oneiric vision of Christ in Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951, Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow) share a triangular configuration, which is formed by the lines connecting Christ’s head, his arms, and the horizontal bar of the Cross. According to Dalí’s concept of nuclear mysticism, this configuration evokes the true shape of the atom. In this sense, Christ’s head is its powerful nucleus. Dalí developed such ideas after World War II as a result of his deep interests in atomic science, Catholic mysticism, and classical painting. Following his first private audience with Pope Pius VII in Rome in 1949, he announced his intention to guide modern painting back to the great tradition of the old masters and to transmit the ecstasy of God. He sought to realize this ambition by drawing on his personal interpretation of nuclear physics and an exaltation of atomic power. Fashioning himself as a nuclear mystic, he declared himself to have understanding of the ‘forces and hidden laws of things’. Dalí’s provocative attitudes—especially his pro-nuclear stance combined with his sympathy for Franco’s regime—clashed with the position of most of his peers, ultimately leading to his defamation by the Surrealist group in 1960.

The lithograph belongs to a series of 105 illustrations, which Dalí produced for his friend Giuseppe Albaretto in 1963–64 for a modern edition of the Bible. Titled Biblia Sacra, it was published in five volumes by Rizzoli between 1967 and 1969 and re-published in later editions in Barcelona, Paris, and Germany.

Click to zoom and pan

Click to zoom and pan

...

Your feedback is very important to us. Would you like to tell us why?

We will never display your feedback on site - this information is used for research purposes.

Artwork Details

Title

Tolle, tolle, crucifige eum, (‘Take him away! Take him away! Crucify him!’), Pl. 48 in Vol. III of Biblia Sacra (Milan: Rizzoli, 1967–69), 5 vols.

Artist

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech (Figueres, Catalonia, 1904–89).

Date

1967–69.

Medium and Support

Colour offset lithograph.

Dimensions

48 x 35 cm.

Marks and Inscriptions

‘Dalí 1964’.

Acquisition Details

Unknown.

Previous Owners

Unknown.

Institution

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

Bibliography

Eduard Fornés, Dalí and his Books (Barcelona: Editorial Mediterrània, 1987), pp. 34 & 56;

Dawn Ades, ed., Dalí (Milan: Bompiani, 2004), pp. 354–57, 364–65, & 368–71;

Jonathan Wallis, ‘Holy Toledo! Saint John of the Cross, Paranoiac Critical Mysticism, and the Life and Work of Saint Dalí’, in The Dalí Renaissance: New Perspectives on his Life and Art after 1940. An International Symposium, ed. Michael R. Taylor (Philadelphia PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2008), pp. 37–52;

Michael R. Taylor, ‘On the Road with Salvador Dalí: The 1952 Nuclear Mysticism Lecture Tour’, in The Dalí Renaissance: New Perspectives on His Life and Art after 1940. An International Symposium, ed. Michael R. Taylor (Philadelphia PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2008), pp. 53–70;

Eduard Fornés, Dalí-Illustrator (Paris: Les Heures Claires, 2016).