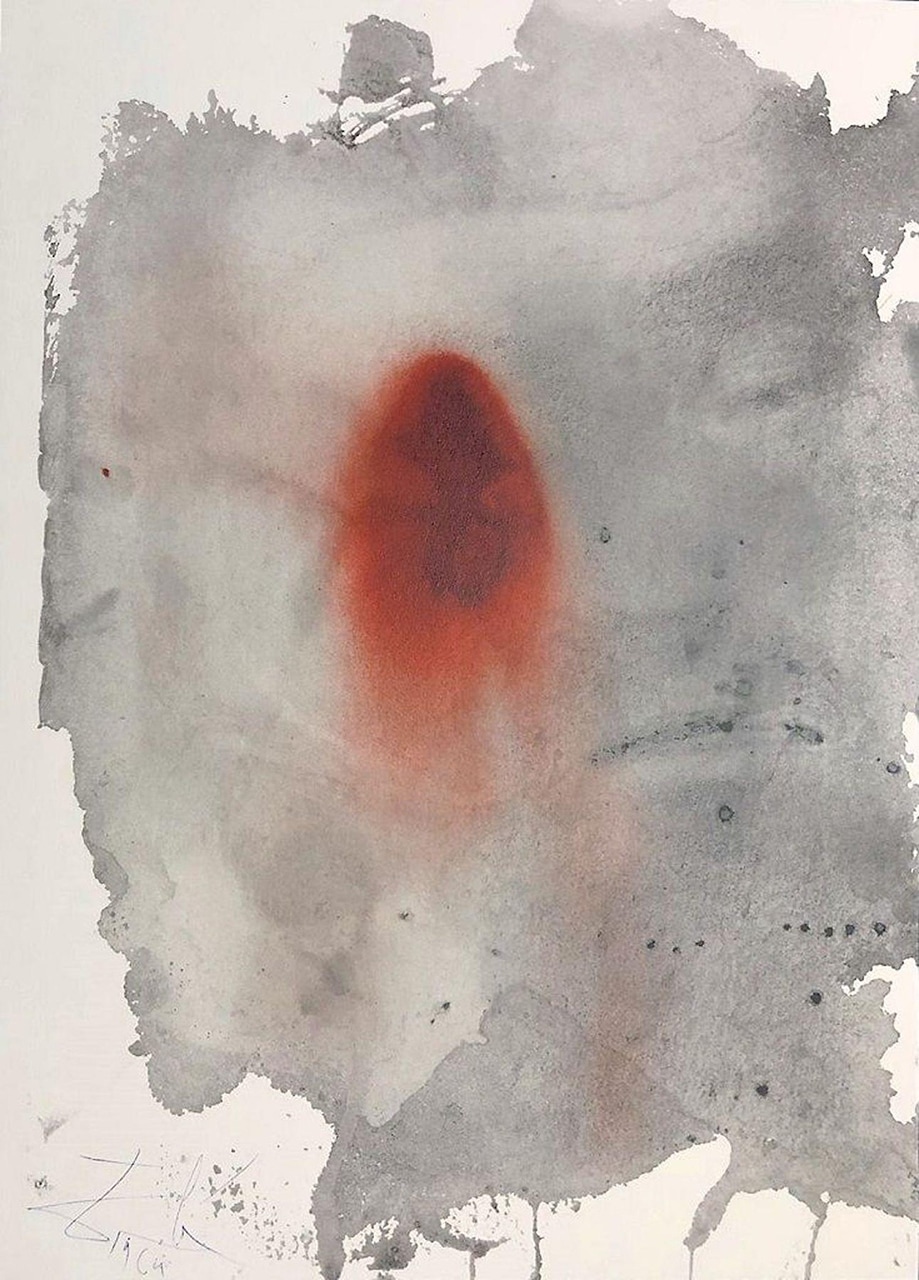

Ego sum vermis et non homo

Published between 1967 and 1969 as part of a five-volume series of highly personalized reflections on questions of faith and devotion, Dalí’s self-portrait draws its inspiration from two verses in the Vulgate or early Latin Bible. The first, taken from Psalm 21:7 in the Old Testament (given in more recent versions as Psalm 22:6), adopts the image of the worm as a way of drawing attention to the insignificance of human endeavour and the feeling of communal alienation: ‘Ego autem sum vermis, et non homo; opprobrium hominum, et abjectio plebis’ (‘But I am a worm, and no man; a reproach of men, and despised by the people’). The second, in contrast, from Mark 15:37 in the New Testament, alludes to the climactic moments of the Crucifixion, describing how ‘Jesus autem emissa voce magna expiravit’ (‘With a loud cry, Jesus breathed his last’). The composition succeeds as a result in associating the death and alienation of the individual with the death and alienation of Christ, mapping the suffering and pain of the Crucifixion onto the fate that we will all one day be forced to endure.

The sincerity of Dalí’s devotion has been the subject of a long and protracted debate. Having commenced his artistic career by identifying himself as an anti-clerical, anti-establishment communist and atheist, Dalí was regarded—along with figures such as Picasso and García Lorca—as a pillar of the international left-wing avant-garde. His experiments in surrealism, influenced by a reading of writers such Freud, led him to produce a series of frank and shocking insights into questions of religion, morality, and sexual ethics, a notable example being The Great Masturbator (1929, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid). Yet, by refusing to denounce the rise of fascism, Dalí soon found himself alienated from his fellow surrealists before eventually being expelled from the movement in 1939, shortly after the victory of the forces fighting under General Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). It is at this point that Dalí, the former atheist, publicly described himself as an ardent Catholic, a supporter of absolute monarchy, and a figure sympathetic to Franco’s dictatorship—a decision regarded by many merely as a ruse with which to enable him to avoid the fate of colleagues such as García Lorca, who was assassinated by the fascists in 1936. Angered by the betrayal, George Orwell, who was himself wounded while fighting in Catalonia, famously characterized Dalí as ‘a good draughtsman’ but ‘a disgusting human being’.

Irrespective of its broader political implications or the problem of sincerity, Ego sum vermis et non homo can be read alongside religious paintings such as Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951, Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow) as products of a fascination with questions of suffering and pain. The artist, conscious of his mortality, envisions himself in a port-mortem state, contrasting the afflictions of life with the sleep-like serenity of death. The lithograph functions in this sense as a universal, inviting viewers to reflect on the passage of time and the impermanence of all that we habitually take for granted.

Click to zoom and pan

Click to zoom and pan

...

Your feedback is very important to us. Would you like to tell us why?

We will never display your feedback on site - this information is used for research purposes.

Artwork Details

Title

Ego sum vermis et non homo, (‘But I am a worm and not a man’) from his Biblia Sacra (pl. 49), published between 1967 and 1969.

Artist

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech (Figueres, Catalonia, 1904–89).

Date

1964.

Medium and Support

lithograph on paper.

Dimensions

48.26 x 34.93, cut from his Biblia Sacra (5 vols) published in Rome by Rizzoli Editoris.

Marks and Inscriptions

Signed ‘Dalí 1964’.

Acquisition Details

Unknown.

Previous Owners

Unknown.

Institution

St John’s College, Durham University.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, DACS 2022.

Bibliography

Gilles Néret, Salvador Dalí, 1904–1989 (Cologne: Taschen, 1994);

Eric Shanes, The Life and Masterworks of Salvador Dalí, 2nd ed. (New York: Parkstone International, 2010);

Eric Shanes, Salvador Dalí (New York: Parkstone International, 2014).